With Those Same Boots of Lead Again

A disquisitional reading of a classic Dickinson poem past Dr Oliver Tearle

'I felt a Funeral, in my Brain' is poem number 280 in Emily Dickinson's Complete Poems. This intriguing poem presents a number of enigmas for the reader, like many of Emily Dickinson's poems. In this post it is our intention to offer a short summary and analysis of 'I felt a Funeral, in my Brain' and to try to clear abroad some of the obscurities and ambiguities.

I felt a Funeral, in my Encephalon,

And Mourners to and fro

Kept treading – treading – till it seemed

That Sense was breaking through –

And when they all were seated,

A Service, like a Pulsate –

Kept beating – beating – till I thought

My heed was going numb –

And then I heard them elevator a Box

And creak across my Soul

With those same Boots of Atomic number 82, again,

Then Infinite – began to price,

As all the Heavens were a Bell,

And Beingness, only an Ear,

And I, and Silence, some foreign Race,

Wrecked, solitary, hither –

And and so a Plank in Reason, broke,

And I dropped down, and down –

And striking a World, at every plunge,

And Finished knowing – then –

A brief summary of the poem chop-chop reveals how odd it is, even by Emily Dickinson's wonderfully eccentric standards. But then 'I felt a Funeral, in my Encephalon' is about going mad, about losing i's grip on reality and feeling sanity slide away – at least, in one interpretation or assay of the poem.

In the commencement stanza, the poem's speaker uses the metaphor of the funeral for what is going on inside her caput (we volition assume that the speaker is female person here, though this is merely surmise: Dickinson often uses male person speakers in her verse). Her sanity and reason have died, and the chaos inside her mind is like the mourners at a funeral walking backward and forward.

The insistent repetition of 'treading – treading' evokes the hammering and turbulence inside the speaker'south brain. These mourners sit and the service takes place, featuring first a drum chirapsia and then – following the creaking elevator of the chapeau of a box – a sound that reminds the speaker of a bell (suggesting the tolling of a funeral bong to announce someone's death).

Yet, as and so often with an Emily Dickinson verse form, the meaning is not – cannot – be every bit straightforward every bit this. The funeral suggests the loss of something, but is it reason and sanity that are lost, or is information technology reason and sanity that kill off something else? Who, or what, is this 'Funeral in my encephalon' for? The verse form withholds this information.

Yet, as and so often with an Emily Dickinson verse form, the meaning is not – cannot – be every bit straightforward every bit this. The funeral suggests the loss of something, but is it reason and sanity that are lost, or is information technology reason and sanity that kill off something else? Who, or what, is this 'Funeral in my encephalon' for? The verse form withholds this information.

Note how at the end of that outset stanza, Dickinson's speaker says that 'it seemed / That Sense was breaking through'. If sense – common sense, reason, sanity – is breaking through, that could suggest that they are making progress, that sense is acquisition irrationality and it is unreason, rather than reason, that has died.

This is, perhaps, an inevitable role of getting sometime: we lose our sense of fun, our childlike irrationality every bit our mind hardens into reason and sense (and being sensible). Function of the trouble lies in how nosotros view the phrase 'breaking through', which could either mean 'coming into view' (similar a shaft of sunlight through a gap in the defunction) or 'falling and collapsing' through something, such equally the floorboards. (Note, in this connection, the image of the 'plank' afterward in the poem.)

What's more than, a funeral is traditionally a solemn and sober affair, formal and orderly: more than evocative of sensible reason than wild irrationality. If irrationality (or madness) had cleaved through and taken over instead, wouldn't we expect something more chaotic and hell-raising to exist going on than a funeral, with the mourners 'seated' and the mind going 'numb'?

The latter parts of the poem seem to suggest that we were peradventure correct first fourth dimension, however, and that the speaker has lost her mind: the speaker finds herself along with 'Silence', solitary like a shipwrecked person. And then, perhaps helped along by this solitude and silence, a 'Plank in Reason' bankrupt, and the speaker describes the post-obit awareness equally similar falling through the floor. She loses her sense of being grounded and stable, falling 'down, and down'. Information technology appears that she has lost her reason. Yet the final line of Dickinson's verse form is ambiguous:

And Finished knowing – and so –

'Finished knowing' as in stopped knowing something, or concluded up by knowing something? 'Finished knowing' is cryptic. Does the speaker gain or lose noesis at the end of the poem? And if she does gain knowledge, knowledge of what?

'I felt a Funeral in my Brain' is one of Emily Dickinson's about puzzling poems in that its meaning could exist interpreted in two very divergent means. The ambiguities aren't merely a matter of difference in meaning, but of sheer opposition. Whose funeral is it anyway? Our analysis cannot answer that question. Nosotros welcome your thoughts on a truly troubling, but brilliant, verse form.

About Emily Dickinson

Peradventure no other poet has attained such a loftier reputation after their death that was unknown to them during their lifetime. Built-in in 1830, Emily Dickinson lived her whole life within the few miles around her hometown of Amherst, Massachusetts. She never married, despite several romantic correspondences, and was better-known as a gardener than equally a poet while she was alive.

Nevertheless, it'southward non quite true (as it's sometimes alleged) that none of Dickinson'south poems was published during her own lifetime. A handful – fewer than a dozen of some i,800 poems she wrote in total – appeared in an 1864 anthology, Drum Beat, published to raise coin for Spousal relationship soldiers fighting in the Civil War. But it was iv years after her death, in 1890, that a book of her poetry would appear before the American public for the kickoff fourth dimension and her posthumous career would begin to take off.

Dickinson collected effectually viii hundred of her poems into little manuscript books which she lovingly put together without telling anyone. Her poetry is instantly recognisable for her idiosyncratic use of dashes in place of other forms of punctuation. She frequently uses the four-line stanza (or quatrain), and, unusually for a nineteenth-century poet, utilises pararhyme or half-rhyme equally often as full rhyme. The epitaph on Emily Dickinson's gravestone, equanimous by the poet herself, features just ii words: 'chosen dorsum'.

Continue to explore Dickinson's poetry with Dickinson's wonderful serpent poem, 'A narrow Young man in the Grass', her 'My Life had stood – a Loaded Gun'., and her verse form 'Considering I could not stop for Decease'. If y'all want to own all of Dickinson'south wonderful poetry in a single volume, you tin: nosotros recommend the Faber edition of her Consummate Poems .

The writer of this article, Dr Oliver Tearle, is a literary critic and lecturer in English language at Loughborough University. He is the author of, among others,The Secret Library: A Volume-Lovers' Journey Through Curiosities of History andThe Great War, The Waste Land and the Modernist Long Poem.

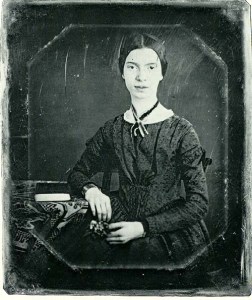

Image: Black/white photograph of Emily Dickinson by William C. North (1846/7), Wikimedia Eatables.

Source: https://interestingliterature.com/2016/11/a-short-analysis-of-emily-dickinsons-i-felt-a-funeral-in-my-brain/

0 Response to "With Those Same Boots of Lead Again"

Post a Comment